“In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.” (attributable to either Warren Buffett or Benjamin Graham)

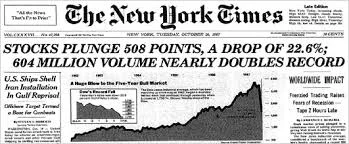

The old adage that in a rising tide all boats float feels an apt description for today's market. In our race to new highs we carry along a series of assets that in a "normal" market would not fare as well.

Yet, as I have said before, there is no point standing in front of speeding trains...regardless of whether or not there is an engineer steering the locomotive.

Today we are bombarded about other higher yielding opportunities. Seminars abound about investing in ICOs. Margin and leverage have come back into the vernacular as investors see nothing but a bull market ahead (despite the recent pickup in volatility).

I laugh as I watch ICOs now being packaged as portfolios and utilizing the same distribution systems normally left to conventional investments. I described this recently to the press as “trying to move an automobile through a slaughter house”. Conceptually, on a white board it should work, but the industrial machinery will break down.

So, to quote one to my favorite movies “Mascots”: “Those that can’t do teach. And those that can’t teach, teach gym. And those that can't teach gym, teach drivers ed." (Video link here)

From an investment practitioner’s perspective, we seem to be in drivers ed, which begs the question:

Are we in a fool’s market?

In order to make money does one have to be completely IRRATIONAL to make successful investments?

Sadly, when looking at the market tape, it appears more and more that irrationality rules the day.

We can look no further than the American Presidency to see this at play with government policy.

Joe Kennedy’s old quote was to sell stocks when the shoe shine boy tells you to “buy”. Now, I hear folks readily rolling out Nixon’s “mad man theory” as a rationale for today’s environment.

Has the general populace decided that Nash’s Nobel prize winning work is now the explanation?

Possibly. Our search for an investment narrative continues as behaviorally we all need an explanation (Look no further than the terrific book Sapiens for more such explanations).

When I look at valuations today, it is clear that what is cheap on a relative basis is Asia. Extending that analysis further, I could also make the case for emerging markets.

But, that is on a relative basis, in a market absolutely (pardon the pun) over-valued.

I had coffee with David Kuo, CEO of Motley Fool for Asia this week, and he reminded me of the old Warren Buffett quote: “I’d be a bum with a tin cup if the markets were always efficient”.

Yet, how should investors protect themselves with regards to valuations? It is by any measure, an expensive market.

David's words were prescient again:

"Over the long term, the value of a company will be determined by the profit and cash flow it is able to generate.

Consequently, one must be able to estimate with some degree of cynicism the profit and cash that the company is capable of producing from now to eternity.

Discount it back to today with a healthy dose of growth skepticism for a generous margin of error. The bigger the margin of error, the greater the margin of safety."

Focusing on a relative basis, Asia certainly looks cheap. Specifically, Asia and emerging markets look cheap.

I spoke recently with Yoojeong Oh, Investment Manager – Equites Asia for Aberdeen. She and her team manage two portfolios that I like to follow: The Aberdeen Global – Asia Pacific Equity Fund and The Aberdeen Global – Asian Smaller Companies Fund. You can click on either hyperlink to learn specifically more about each fund.

Now full disclosure to my new readers. I may be slightly biased with Aberdeen, as you all know that deep down I am a value investor at heart.

But, as a “data guy”, the data is clear. On a relative basis, Asia and EM are cheap. Here were some of UnHedged’s questions to Yoojeong Oh of Aberdeen:

UnHedged: When looking at the Asian markets, should investors now look more carefully at domestic growth?

Yoojeong Oh: We have been very much positioned towards domestic growth. Our funds have been underweighted in markets like Taiwan and Korea where they are more export driven and dependent. There is a much stronger story following the demographic story, the population story, the growing middle class, and rising incomes. You can see that in India with a growing local consumer base and much less exposure to the US dollar.

We have always wanted to be positioned towards the growth of the Asian consumer in our funds. This has served us well over longer time horizons (our average holding period is 5 years). When you look at growth prospects in Asia, using the IMF growth expectations for Asia, there is a concern that China is going to slow, its growth is still quite high on a global relative basis. In SE Asia we are still seeing good growth rates, and see no need to overweight on firms driven by exports.

UnHedged: That’s interesting that the consumer story in Asia is now developing for investors to follow. But this begs an interesting question, given relative valuations, aren’t Asian equities still cheap?

Yoojeong Oh: If investors were to look at valuations across the region on a P/E and P/B basis, they would find confirmation of that lower relative valuation. Across the globe, all valuations are at historically higher levels, or premium, than average, but as you look across geographies, we are still looking at valuations that are reasonable in Asia.

Asia’s outperformed MSCI World by almost 17%, and we are still seeing better earnings growth which is supporting forward multiples as well.

UnHedged: Let’s expand on that for a second. One could argue that the US is very focused on PE expansion. Is it the same for Asian equities? Or is there true growth?

Yoojeong Oh: There are some risks in the Asian markets that we do need to be mindful of. The US’ tax reform could provide investors with an incentive to re-allocate more to US equities versus their Asian counterparts. In addition, if rates are increasing there is also that as a compelling feature for investors to consider.

But as investors look closer to US stocks versus Asian, there are some key subtleties. When looking at US corporates they use buy-backs which helps their earnings per share. The components of share price momentum in Asia are quite different, it is earnings growth. investors have not seen that as much in the US markets. In Japan and Europe, investors would note more of foreign exchange as a contributor to share prices.

These are all quite different compared to Asia where it has been driven primarily by top line growth which has fed into earnings growth

UnHedged: Should fund investors be concerned about currency risk in light of an implied US policy tilt towards a weaker US dollar?

Yoojeong Oh: There will obviously be companies that have currency risk in regards to their raw materials, but we rely on the companies to hedge that risk themselves. We have chosen to focus mostly on those companies that will benefit from home consumer demand growth in the fast growing south East Asian economies, we have less exposure to the export driven companies found in North Asia and this makes the fund less exposed to US currency moves. We do however monitor our holdings' abilities to hedge this risk themselves at the stock level.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

As we look at Yoojeong’s comments above we can see that if we agree that Asia looks cheap, investors stand to gain. Key to that will be for investors to incorporate the “margin of safety” that David Kuo emphasized.

I personally believe that as the market continues its march forward, irrespective of the speeding locomotive, investors will inevitably tilt and overweight to Asia.

I am speaking again later this month at a closed door event for UBS management on March 27th. While I cannot invite you, I expect I will have several other new speaking engagements shortly. My last talk for the Mortgage Innovation Summit with the RFI Group in Sydney was terrific and the feedback was great.

Lastly, book wise, I am really enjoying The Gatekeepers by Chris Whipple. I strongly recommend it for the readers who are real policy wonks!

Have a great week ahead!